How do cultures, and societies evolve? Why? Why do cultures evolve in different ways? Are all cultures evolving toward the same thing? Is that evolution a good thing?

In my Cultural Anthropology class, we have been discussing notions of unilineal evolution, and how this theory that all cultures move in the same way from savagery to civilization is one most anthropologists have moved away from as it is quite ethnocentric. I, too, find this grossly oversimplified, but it is hard to ignore the waves of progress that has been made over the course of human history and the tremendously positive impacts they have had. Human-driven advancements in agriculture, wealth, medicine, and technology have all played their role in helping societies liberate themselves from hunger, poverty, and insecurity.

It is not fair to rank cultures in any universal way, but there are some themes in evolution that apply fairly universal positive outcomes. When we try to imagine a better world, probably everyone has similar thoughts that essentially involve eliminating suffering. There are fairly universal levels of advancement that we’re all climbing. Think Maslow’s Heirarchy of Needs for a human-scale model, or Big History for a model that spans the universe. It makes me wonder what levels of advancement lie in our future.

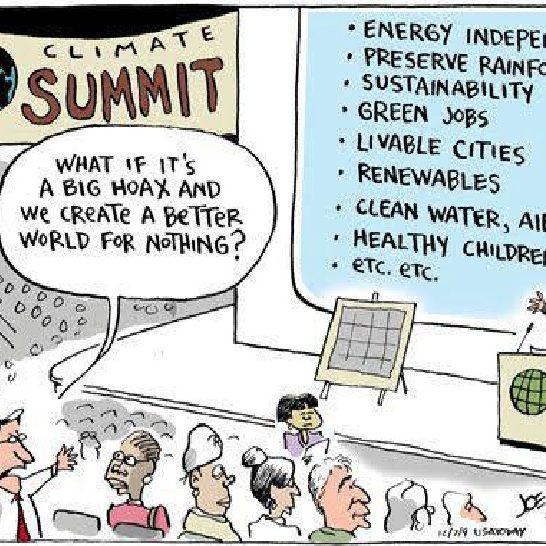

I have always been fascinated with notions of the future, thinking up ways to create a better world through innovation, technology, and advancements in scientific understanding that would help us optimize ideals such as happiness, justice, freedom, truth, peace, and love. When learning about climate change and the massive amounts of damage we are doing to the planet, its species, and ourselves, I tend to take a fairly catastrophic view. We have one shot, if we expect to be here long enough to create the beautiful future we want, we probably should get moving ASAP.

But maybe I’m listening to the “sustainability” arguments, more than the “resillience” and “adaptability” arguments. Taking a huge step back, I realize I might be losing perspective. Look at how far we’ve come. Not just in the past several hundred years, but in the past few decades. I’ve always had a tremendous amount a faith in the advancements of today and tomorrow to have unexpected, miraculous impacts. So why do I treat environmental issues differently? Latour, in our recent reading of Love Your Monsters, puts it well: “Why do we feel so frightened at the moment that our dreams of modernization finally come true?”

Many people, myself included, tend not to view modern technology, such as phones or genetic engineering, as very natural, whereas things like agricultural infrastructure, basic tools, even telescopes and the printing press, aren’t so far away from “natural.” Our culture tends to view itself as advanced, yet incorrectly separated from nature, while other, “developing” cultures are not so well off, but are intimately “connected to nature” in ways we aren’t. Shellenberger and Nordhaus remind us that “[m]any environmentally concerned people today view technology as an affront to the sacredness of nature, but our technologies have always been perfectly natural.” We grow and change with our environment just as our environment grows and changes with us. Mother Nature is strong, adaptive, and resilient.

I used to be fairly hard against genetic engineering, synthetic meat (even though I’m mostly vegetarian), and geoengineering. But recently I’ve been feeling less negative about these as potential solutions. I tend to be indecisive because I’m afraid to make the wrong choice. But maybe taking the wrong path is better than taking the left one and not taking a path at all. We are so stuck lately arguing among ourselves that no path is chosen. We forget that if we try something and it throws an unexpected consequence at us, we can adapt and adjust.

“What we call ‘saving the Earth’ will, in practice, require creating and re-creating it again and again for as long as humans inhabit it.”

Shellenberger and Nordhaus, Love Your Monsters

Climate change is the biggest of many disastrous unintended consequences of our modern world. Coal power, population growth, increased wealth and consumerism, aren’t inherently wrong — they allow for modernity in a way that we appreciate. But they have reached a level of harm that we can’t keep up with, and cannot continue. And just because they “failed,” doesn’t mean technology and our advanced human society are the wrong idea, it just means that we have to design something better.