Indigenous Approaches to Nature Religion, Environmentalism, and the Material-Spiritual Forces of Life in Cascadia

The Salmon is one of the Pacific Northwest’s most iconic and best known symbols. Salmon have been central to the region’s cultural, economic, spiritual, and environmental histories, both of Indigenous tribes and of post-colonial inhabitants. Investigating the role of Salmon in the religious history of the Pacific Northwest reveals ways that spiritual and cultural relationships with the natural environment are not just ideological or symbolic, but are grounded in the physicality of one’s experience living with this land and the way that both symbol and fish itself are consumed and embodied by those who reside here. Religion is often understood through ideas and beliefs, rather than material, embodied existence — even Albanese’s concept of nature religion is oriented to conception of nature over experience in nature. In this piece, I hope to consider what an approach that centers physicality may bring to an understanding of spiritual life in the Pacific Northwest.

I’ll start by illustrating the value of studying Salmon in a religious studies course: my goal in this work is to expand my idea of religious studies to include “interdisciplinary” ideas. This project fits into a larger trend in my current studies, as I operate at the intersection of religious studies and environmental studies, two fields which are defined by their topics over their methods, and which are often seen as unrelated. In studying Salmon, I hope to expand and articulate ways in which environment and religion, two “big words” mutually create one another. Salmon, both the species and the symbol, are a locus which joins social, cultural, economic, religious, and environmental meanings and challenges. Through this project, I will apply arguments from Durkheim about the power of symbols in religion; Albanese’s concept of “nature religion” which she uses as an pattern-detecting tool in understanding the region’s spiritual-scape; and a more general approaches of embodiment and natureculture which center the body as the locus of culture and which explains the ways spiritual meanings and the material/ecological realities are mutually creating in human culture.

Spiritual Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest is known nationally as a region with the greatest number of religious “nones,” individuals who don’t affiliate with a particular religious group. The region’s religious landscape has been characterized as diverse, individualistic, ecumenical, spiritually curious and exploratory, lacking a dominant religious social mirror, noncommittal, mobile, and nature-oriented (Killen & Silk 2004). Another trend in the region is the prevalence of people who identify as “spiritual but not religious.” Mark Shibley breaks this down into Apocalyptic millennialism, New Age spirituality, and Earth-based spirituality (Killen & Silk 2004). While religion is not unimportant to the region, residents engage with concepts of spirituality in ways which challenge what it means to be religious (Todd 2014). Regardless of religious, spiritual, or secular identity, Pacific Northwesterners share in a common reverence for nature (Albanese 1991; Todd 2014; Killen & Silk 2004). To Cascadians, nature is sacred, wilderness is sacred (Todd 2014). This is seen most clearly in indigenous spirituality, environmentalism, and even secular portrayals of the region. The Salmon, I argue, is a sacred symbol which draws together these various groups and illustrates not just the spiritual character of the region, but the ecological basis for nature reverence and spiritual life in the Pacific Northwest.

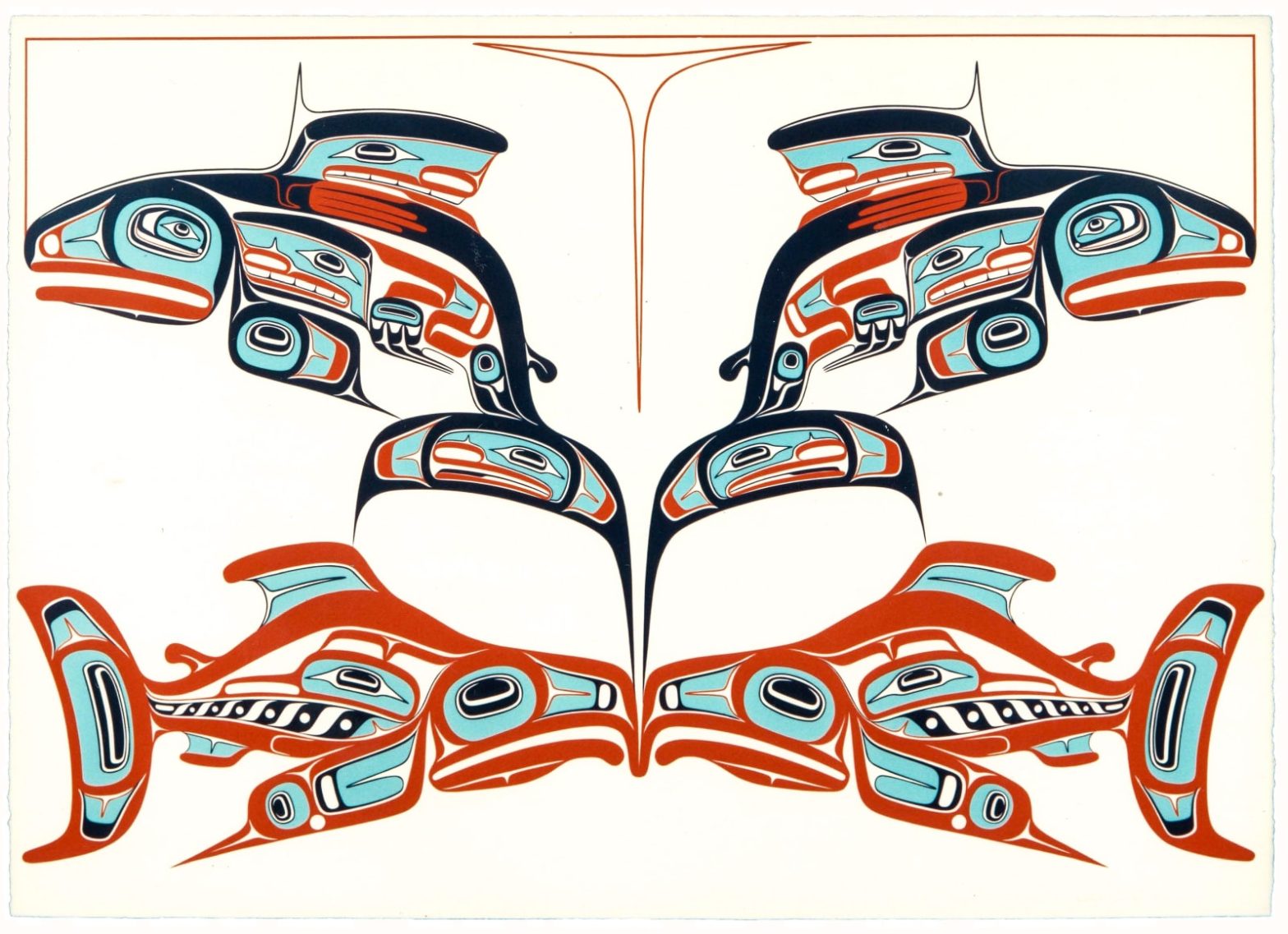

Indigenous Spirituality and the Sacred Salmon

Indigenous Peoples of the Columbia River Basin collectively refer to themselves as Wy-Kan-Ush-Pum, or Salmon People (CRITFC). For at least 10 thousand years, indigenous peoples of what is now called the Pacific Northwest have organized their lives around Salmon (Community Alliance 2018). Their trade economies and political systems, inter-tribal relations (CRITFC), even gender roles (White 1996) center Salmon. Salmon was a being of deep spiritual importance to these cultures. One tribal legend tells of a time when their Creator asked who would help the humans live, since“would be quite helpless and require much assistance from them all.” Salmon was the first to come forward to offer their body as a gift to nourish the people, and the Water offered to be a home for the Salmon. “In accordance with their sacrifice, these two receive a place of honor at traditional feasts throughout the Columbia Basin”: Salmon ceremonies begin with a blessing and the drinking of water, a prayer of thanksgiving, and the serving of wy-kan-ush, the Salmon (CRITFC). The First Salmon Ceremony is aimed at ensuring the return of the Salmon and honoring its life-sustaining force. As Umatilla tribe member Antone Minthorn reflects, this ceremony is “ an appreciation that the salmon are coming back. It is again the natural law; the cycle of life. It’s the way things are and if there was no water, there would be no salmon, there would be no cycle, no food. And the Indian people respect it accordingly” (CRITFC). Other stories describe the Salmon as immortal beings living in the ocean. In “springtime, these immortal humans put on Salmon disguises to offer themselves as food to the people. After the Salmon were eaten the people would put the full fish skeleton back in the water in the belief that its spirit would rise again and turn back into Salmon people, thus creating the cycle of life” (“Spirits of the West Coast”).Emile Durkheim’s functionalist approach to explaining religion and theory of religious ritual, still one of the most influential in the field of religious studies, would understand the Salmon to be a totem of indigenous religion. Durkheim’s most basic argument is that humans are irreducibly social and thus that religion is a system of beliefs relative to sacred things, as opposed to “the profane” (Preus 1987). Durkehim says religion or religiosity is continually caused: he says that the object of religious veneration is society itself, and the totem or symbol which is honored in ritual, represents society as a whole. The deep emotion felt by people during ritual, “collective effervescence,” makes the item sacred because it represents the dependence of the individual on the group. The way this would apply to the salmon case is obvious. He’s trying to illustrate a social function of religion: to maintain social cohesion. Durkheim’s theory was developed in a capitalist context of individualism and a shared obsession with freedom, which he saw tearing society apart (Preus 1987). Durkheim’s disciplinary inheritance, as many RELS scholars, is one which depends on a post-colonial separation of religion out of the rest of life, which would be called the secular sphere (Cavanaugh 2009). While Durkheim’s understanding of the Salmon symbol is useful in contextualizing the power of ritual in human communities, a humbler look at indigenous spirituality and an investigation into the material importance of Salmon illustrate disciplinary blind spots in the approach to understanding “religious” life, meaning, and culture, especially in the Pacific Northwest.

Salmon as a Keystone Species

The Chinook Salmon, also known as the King Salmon, is Oregon’s State Fish. Chinook are one of seven indigenous species of “salmon” in the genus Oncorhynchus in Oregon and Washington, along with (chinook, coho, chum, sockeye, and pink salmon, and steelhead and cutthroat trout). Chinook grow 3-5 feet long and weigh 30-110 pounds. They live in the region ranging from California to Alaska and spend their lives in many different habitats: salmon hatch in fast-moving freshwater rivers and streams, move to estuaries as juveniles, spend their adult lives in the open ocean, and make the long, tough journey upstream to lay their roe in the exact same place in the stream where they were born, known as “ancestral homewaters.” In this way, “Salmon act as an ecological process vector, important in the transport of energy and nutrients between the ocean, estuaries, and freshwater environments” (Cederholm 2000). They essentially are a “virtually free gift to the energy ledger of the Columbia” from outside the river system, in the form of nutrition (White 1996). Their bodies feed indigenous communities and/or die after laying, allowing their bodies to decay and enrich their streams with nutrients gained from their lives hundreds of miles away in the oceans (White 1996). “As a seasonal resource, salmon directly affect the ecology of many aquatic and terrestrial consumers, and indirectly affect the entire food web, [thus] supporting overall ecosystem health” (Cederholm 2000). It is for this critical role they play in the entire bioregion’s ecosystem that they are known as a “keystone species:” “Salmon and wildlife are important co-dependent components of regional biodiversity” (Cederholm 2000). Without salmon, “not only the lives of bears, ospreys, bald eagles, martens, wolverines, frogs, salamanders, and even deer and other herbivores would be vastly different if not impossible, but also the livelihood of trees, the productivity of the forest floor, and the insects that are at the base of the food chain would be imperiled without the energetic input of salmon. The annual massive die out of salmon has created the most biologically diverse forest on Earth” (Molinero and Garcia).

This simplified explanation of how Salmon fit into the bioregion’s ecosystem suggests that the spiritual importance of Salmon to indigenous groups may have biological and empirically supportable grounding. Chief Weinock of the Yakima reflects: “My strength is from the fish; my blood is from the fish, from the roots and berries. The fish and game are the essence of my life. I was not brought from a foreign country and did not come here. I was put here by the Creator” (CRITFC 1915). Salmon literally are the lifeblood of indigenous bodies, economies, social structures, and spiritual traditions. The sacredness of the salmon doesn’t just operate as a symbol or totem representing the dependence of individuals on their group, as Durkheim would argue. Indigenous individuals and cultures literally do depend on salmon. Salmon being consumed by the bodies of humans, and humans embodying salmon in ceremonial dance, are not just symbolically related but are mutually causing physical/ecological realities upon which indigenous culture and life depends. “As the salmon dwindle and environmental crises deepen, there is an understandable tendency to romanticize and even invent pasts in which the planet was nurturing and humans simply accepting and grateful… Salmon have sustained culturally rich human communities whose way of life stretches back over five thousand years. But the people who awaited the salmon were not simple fisherfolk gratefully taking the bounty of their mother earth. Culturally, they made no assumption about the inevitability of the salmon’s return. Their rituals, their social practices, their stories all recognized the possibility that the fish would fail to appear. They waited for salmon not with faith but with anxiety” (White 1996, 18). The rituals they performed, including fishing (CRITFC), dances (Brauer), ceremonies (PBS), and treatment of the dead Salmon’s bodies (White), were about sustaining life and they “acknowledged [the role of death in sustaining life] and compensated for it by treating with reverence and respect, in a controlled ceremonial context, those things which, if uncontrolled, could cause the salmon to disappear” (White 1996, 18).

Salmon Uniting Humans and Nature

This overlap of material and spiritual reality in the indigenous relationship to salmon shines light on another blind spot in the field. Catherine Albanese’s work on tracing “nature religion” says that reverence for nature is a dominant theme in the history of religious life in the Pacific Northwest, and which serves as a social mirror (Albanese 1991). As discussed earlier, respect for nature is indeed a common theme among all sorts of people and periods in the region’s history. However, nature is often discussed, by Albanese and others who engage with this concept, in ideal or belief-oriented terms. Albanese analyzes the symbol of nature in various modes of thought and traditions from pioneers, to folk music, to transcendentalists: “on the one hand, nature seemed to encourage the pursuit of harmony, as individuals sought proper attunement of human society to nature and thus mastery over sources of pain and trouble in themselves and others. And yet, Nature Religion fostered more ambivalent themes of fear and fascination for wildness and, at the same time, an impulse toward its dominance and control … this complicated rhetoric of the symbol is most clearly expressed in the alliance of nature religion with the politics of nationalism and expansion” (Albanese 1991, 12, my italics). As the indigenous relationship with salmon illustrates (other materially focused analyses of the region which we’ll get to), this treatment of Nature as a symbol doesn’t tell the whole story.

Indigenous lives were materially and spiritually enmeshed with Nature as is evident in the Salmon story. This separation of “Nature” would not have made sense to the pre-colonial Indigenous mind. To them, nature “was being” and “the destruction of [Earth], or the forced separation from it, would be a soul-searing, emotional ordeal” analogous to death (Josephy 2007, 114). The spiritual construction of their personal and collective sense of meaning was based intimately in their relationship with what is now known as Nature, so much so that a concept of Nature Religion makes next to no sense when applied to a pre-colonial Pacific Northwest culture. Additionally, the very concept of religion, as an aspect of culture that could be separated from “secular” life, would not have made sense in a pre-colonial, pre-protestant reformation context like the Columbia River Basin. As William Cavanaugh argues in a historical tracing of the concept of religion, there is no transcultural, transhistorical concept of religion but something imposed by Westerners on much of the rest of the world during colonization, and thus the attempt to apply religion outside of this context (as a neutral category) is a configuration of power tied up with a Protestant, liberal nation state (Cavanaugh 2009, 59-60). Attempts to understand indigenous “nature religion” or indigenous “religion/religious belief” at all, by nature of definition, fails to recognize how spiritual and material realities were inseparable in indigenous life and to an indigenous worldview. While indigenous understanding of Salmon may contribute to their social functioning, Durkheim and Albanese’s theories of religious ritual and reverence for nature sees this in symbolic terms.

Both Durkheim and Albanese assume religion and nature as binary opposites to non-religion and non-nature, a dichotomy that fits a Western and scholarly worldview but which fails to fully explain indigenous life which existed here for so much longer. The salmon, or what we may separate as “nature” or a “totem” is something with which indigenous people coevolved for generations and which they do literally depend on. So, I argue that it is more useful and more accurate to consider indigenous humans and culture as embedded within nature, and, in so doing, explore the ways the field of religious studies could benefit from adopting an approach which emphasizes materiality and ecological analysis. The concept of “natureculture,” coined by feminist scholar Donna Haraway is useful here, as it synthesizes nature and culture in a way “that recognizes their inseparability in ecological relationships that are both biophysically and socially formed” (Malone et. al. 2016). Evolutionarily, the entire Cascadian bioregion coevolved with Salmon and indigenous human communities, and in ways that informed indigenous culture and spirituality, which through ceremonies and practices further supported the ecological wellness of the region. This is the “natural law; the cycle of life” (CRITFC). Durkheim’s theory thus is challenged to treat “nature” as part of the “society” upon which human cultures depend. And Albanese’s nature religion must engage in deconstructing the influence of these Western dichotomies on both spiritual and material realities of the region. I’ll start this process as I trace the Salmon’s importance in other contexts.

Fishing: A Lived Religion

Fishing has a deep history in the Pacific Northwest. It is one of the most popular ways modern Cascadians spend time in Nature, but indigenous peoples of the region fished along the Columbia and its tributaries long before that. Fishing is often seen as recreational and economic, but is often associated with environmentalism, has been described as a “lived religion,” and offers many other ways of tracing spirituality’s intersection with “secular” life. Historically, indigenous people ate about a pound of Salmon a day (CRITFC). Fishing was the activity upon which river communities and those they traded with depended. Indigenous groups were guided by elders and chiefs who set rules about how many salmon could be harvested each day, and during the season, all of which depended on complex cultural norms and an ability to read salmon behavior, numbers, and the water (CRITFC). Columbia River Natives fished at Celilo Falls, a site which has since been buried because of the erection of dams in the Gorge. According to the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, “during the spring flooding, ten times more water passed over this spectacular waterfall than passes over Niagara Falls today.” For thousands of years, Celilo Falls, known as Wy-am, “was one of history’s great market places. A half-dozen tribes had permanent villages between the falls and where the city of The Dalles now stands. As many as 5,000 people would gather to trade, feast, and participate in games and religious ceremonies (CRITFC). The combination of water, falls, and rapids are providential to indigenous peoples, because without these places where the rocks (caused by Coyote) fell in the river, catch fish would be much less viable (White 1996). The “death” of Celilo was more than 50 years ago, but the spirit of this place lives on through the senses, souls, and traditions of indigenous groups today; Wy-am means “echo of falling water.” A Yakima tribesperson reflects: “Celilo still reverberates in the heart of every Native American who ever fished or lived by it. They can still see all the characteristics of the waterfall. If they listen, they can still hear its roar. If they inhale, the fragrances of mist and fish and water come back again” (Ted Strong, CRITFC).

Many who have reflected on their experiences fishing have used religious language, such as spiritual, sacred, meditative, ritualistic (Snyder 2007). Snyder’s tracing of fly fishing in various situated contexts sees fishing as a “lived religion” which references the everyday experiences and practices of religious people over belief or worldview. Snyder’s description of fishing as a lived religion of nature illustrates a context which broadens the concept of religion in a way that may help to understand the spiritual importance of sensory and visceral experiences of all “outdoorsy” Cascadians in nature. Albanese and other scholars on religion in the Pacific Northwest describe this by saying that rather than go to church, Cascadians spend their weekends camping or going for hikes. Language of “forest as church” and nature as “closeness with God” are part of the common vocabulary of the region, so treating fishing as a religious or spiritual practice would not be considered odd. Fishing, in order to be successful, is a physical activity which depends on tactile and experiential knowledge of a river’s energy system (White 1996). The concept of lived religion as applied to fishing, and nature religion more generally, illustrates one way that spiritual experience is intimately tied with lived experience.

Fishing is not just yummy, profitable, and meditative. Modern issues of indigenous sovereignty and environmental protection intersect with the practice of fishing. Guaranteeing indigenous access to rivers and rights to fish has been an important step in repairing cultural erasure and preserving ancestral wisdom about Salmon fishing techniques and species protection. Industrial fishing in the region, along with the erection of dams in the basin (including 250 reservoirs and around 150 hydroelectric projects), have contributed to the region’s economic and political success (White 1996) at the expense of the pre-existing ecosystemic equilibrium between Salmon, land, and indigenous human cultures.

A US Department of the Interior film from 1949 overviews the “mighty Columbia” and promotes the incredible manpower it took to overcome the river and build dams which would power the region, depicting the same tension that Albanese observes: of nature as powerful and awe-inspiring while simultaneously needing to be controlled (Charlie Dean 2014; Albanese 1991). The film treats the pioneering man as heroic in his power to overcome the energy of the Columbia’s river and harvest enough energy from the Columbia to power the region. The dams were built because federal engineers saw the “potential” energy of the water as a materially useful resource in their conquest of nature as well as a symbolic representation of their God-given ability to overcome nature in an idyllic pursuit of utopian life (Albanese 1991), which depended on energy abundance (White 1996). In the case of dams, nature and culture are also entwined, though it appears in this story that the ideological and religious beliefs of newcomers to the area contributed in a disproportionate and historically new way given the work they did on the Columbia River system and the geologic and impacts of this ideologically-informed material change. Traumas in the form of dams, ecosystem imbalance, and spiritual/cultural pain are felt by the entire natureculture which existed prior. Federally protected fishing rights have been a tiny yet culturally significant step toward acknowledging the ways Western industry and ideology have rapidly eroded thousands of years of balance.

Spiritual Environmentalism: Nature Religion or Religion of Nature?

Responses to this kind of ecosystem degradation have taken many forms in the region. Environmentalism has been particularly passionate and persistent in the Pacific Northwest, especially starting in the 1960s and 70s alongside national movements and discoveries. Of note to the story of Salmon and the sacredness of nature are two categories of environmental activists: transcendentalists and indigenous activists. Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, who is well known for his environmentalism and descriptions of nature, combined Christian, indigenous, and Buddhist spiritual teachings in the interest of environmentalism. Earth-based spiritual groups that follow similar philosophies are present today, and they tend to see personal growth as an aspect of communal and ecological wellness (Todd 2014). Albanese’s nature religion partially explains ways that even secular environmentalists’ reverence for nature informs their ecological activism. But this philosophical quest by environmentalists to find a “religion of nature” is contingent on Protestant visions of an Eden-like ecological Utopia, the ability to define the boundaries of “nature” and “religion.” Indigenous environmental activism has been prevalent in the region for decades but has gone largely unnoticed until a modern wave of Euro-American spiritual interest in nature and finding a “religion of nature” to solve environmental problems. Transcendentalists and the “spiritual and outdoorsy” who romanticise nature in aesthetic and ideological ways contribute to the same imbalance discussed earlier where Protestant visions of nature seem disproportionately active in altering landscapes. The ability to appropriate indigenous beliefs outside of the materially real contexts which informed them further highlights this power imbalance in the region’s history which determines who gets to participate in environmentalism and the creation of a utopian Cascadia.

Mark Shibley’s The Promise and Limits of Secular Spirituality in Cascadia celebrates the benefits of the Earth-based spirituality, but also illustrates its limits. He argues that spiritual individualism, and specifically the New Age focus on the “sacred self,” fails to understand humans and culture as part of nature, unsurprising given our analysis so far (Killen & Silk 2004). While secular groups have had success in Salmon specific protection, thanks to modern scientific progress, the human tendency to try to “speak for salmon” has been an overwhelming failure (Taylor 2009). The complex entanglement of Salmon and indigenous people in this ecosystem, and the late arrival of modern science in the region, make it particularly difficult on secular environmentalism. Indigenous environmental activism has been increasingly influential in advocating for Salmon protections and dam removal. Beyond ecological protection of Salmon, which we now agree is inseparable from the sacredness of Salmon and nature and indigenous lives, reveal a distinct approach to environmentalism as tied up in social justice. The Salmon story is a potent example of what Ramachandra Guha describes as an “environmentalism of the poor,” which dominates the Global South (Guha 2014). Environmentalists of the north, including spiritual ecologists of the PNW and transcendentalists, have prioritized philosophy in creating an environmental ethic and has tended to see humans as plagues to nature. Indigenous activism in the region centers ancestral spiritual wisdom and the lived dependence of indigenous and, now more general Cascadian, dependence on Salmon as a keystone species. The inseparability of humans from nature, and spirituality from indigenous relationships with the natural world, leads to the kind of environmental activism Guha argues cannot be separated from human rights issues. The positioning of indigenous cultures within nature, especially in their activism, allows them to take the lead in a regional question of collective and ecological rights (Todd 2014).

Salmon Nation

This leads me to a final consideration regarding the region’s characteristic Utopianism and the broadening treatment of Salmon as a symbol for what could be. It is hard to imagine another region in the world that identifies itself more strongly with a particular species to the extent that Columbia River Indigenous peoples and modern inhabitants of Cascadia identify with Salmon (Molinero and Garcia). From Washington’s Covid-safety travel signs to Travel Oregon’s robotic Chinook campaign, Salmon are front and center in the region’s marketing strategies and identity. Across time Salmon have been tied to the region’s identity in ways that have spanned geographic, political, religious, and cultural divides. Understanding the power and meaning of the Salmon symbol, both in spiritual and secular contexts, depends on this kind of thick description as I’ve tried to provide. Salmon as a symbol with cultural meaning across the spiritual and cultural landscape is directly tied to Salmon as a keystone species and life-sustaining force in the bioregion.

Tracing the Salmon symbol in this way reveals a symbolic promise embedded in the meaning of this shared cultural marker. The Pacific Northwest was first envisioned by Christian “frontiersmen” who saw the region as an Edenic-like land waiting to be cultivated. In an effort to gain territory and expand populations Westward, the government framed the region as full of an endless supply of untapped natural resources. Families who traveled West moved to create new lives under the promise of freedom, space, and economic prosperity. These utopian visions would inspire religious fervor, experimental communes, and passionate environmental action, many of which were short lived, but the utopian spirit for this land of abundant life, water, and biodiversity would remain strong. The Salmon holds scientific, spiritual, and historical meaning in the minds of Cascadians, bridging the gap between indigenous and Protestant naturecultures. One utopian-esque project, inspired by indigenous wisdom and backed by modern science, merges the spiritual and the physical of the Cascadia Bioregion to envision Salmon as a unifying name for what they call Salmon Nation, a “nature state.” This “state,” unified by Bioregion, thus can be understood as working to undo the myth that the modern nation state is a secular (non-Protestant-biased) institution and the human-nature dichotomy on which its environmentally destructive economy and sense of supernatural power are based (Cavanaugh 2009; Salmon Nation 2019). Their argument “change the name, change the system,” shows the way they are seeking to re-embed humans in nature through symbolic change that centers place, place united by the Salmon-watershed/Cascadia Bioregion (Salmon Nation 2019). Their entrepreneurial appeals to frontierism and utopianism, ecumenical cooperation with secular science and various religio-cultural groups, and non-specific approach to defining this region fits the trends established early on in the spiritual character of the PNW. While vaguely of a nature-religion trend, the work of this organization attempts to return to a pre-colonial unified natureculture, but in a way that is responsive to the ideological and cultural trends of Cascadians’ interests.

A common challenge for Cascadia given its spiritual individualism and lack of social mirror has been in the question of collective rights (Todd 2014; Killen & Silk 2004). This focus on Salmon as a sacred symbol that unifies the region parallels the dependence of the entire region on Salmon and the ecosystem here. The intersection of indigenous history with colonial Protestant history illuminates the disproportionate way imported conceptions of nature, which were centered on instrumental value and individualism, influenced natural ecosystems. The conflict and environmental challenges the region faces today are no-surprise when considering the influence of people whose worldviews were not embedded in or informed by this particular place. Part of what Salmon Nation seems to be attempting, and what may help the region reframe its conversation about collective rights, is the fact that inhabitants still depend in many ways on the Salmon’s ecosystem, or at least will suffer in its destruction. The tendency to still view humans as outside nature, or to see nature religion as belief and not embodied feeling, furthers this divide. Though modern life depends less visibly on local ecosystems, and many of us may depend less regularly on Salmon for food than in centuries past, the physical reality of nature is felt every day in tangible and sensory influential ways by those who live in Cascadia. Focusing on Salmon when considering the spiritual fabric of the Northwest also reveals what is obscured in some of the narratives we’ve engaged with. Environmental degradation, spiritual tensions, social justice, indigenous rights, issues of political power and privilege, and economic models for prosperity all intersect in the story of Sacred Salmon. Through this lense, we seem to see spiritual landscapes as ecological landscapes and regional character as bioregional character.

“Salmon are among the oldest natives of the Pacific Northwest, and over millions of years they learned to inhabit and use nearly all the region’s freshwater, estuarine and marine habitats. …From a mountaintop where an eagle carries a salmon carcass to feed its young, out to the distant oceanic waters of the California Current and the Alaska Gyre, the salmon have penetrated the Northwest to an extent unmatched by any other animal. They are like silver threads woven deep into the fabric of the Northwest Ecosystem. The decline of salmon to the brink of extinction is a clear sign of serious problems. The beautiful tapestry that the Northwesterners call home is unravelling; its silver threads are frayed and broken” (Lichatowich 1999).

Bibliograhy

Albanese, Catherine L. Nature Religion in America: From the Algonkian Indians to the New Age. University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Brauer. Salmon Dance at First Salmon Ceremony – Chilliwack BC June 2011, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D2wfyhi3p8g.

Cavanaugh, William T. The Myth of Religious Violence: Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict. OUP USA, 2009.

Cederholm, et. al. “Pacific Salmon and Wildlife – Ecological Contexts, Relationships, and Implications for Management 2nd Edition | Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife.” 2000. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://wdfw.wa.gov/publications/00063.

Charlie Dean Archives. Columbia River: A Historic Look at The Columbia – CharlieDeanArchives / Archival Footage, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-RBqGWtyFH8.

CRITFC. “Celilo Falls Columbia River | Celilo Falls History.” Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.critfc.org/salmon-culture/tribal-salmon-culture/celilo-falls/.

CRITFC. “Salmon Culture | Pacific Northwest Tribes, Columbia River Salmon.” Accessed November 17, 2020. https://www.critfc.org/salmon-culture/tribal-salmon-culture/.

CRITFC. “Salmon People, Columbia River Indians | Salmon Conservation.” Accessed December 3, 2020. https://www.critfc.org/salmon-culture/we-are-all-salmon-people/.

Community Alliance for Global Justice. “Film: ‘Salmon People’ (2018).” Accessed December 9, 2020. https://cagj.org/salmonpeople/

Guha, Ramachandra. Environmentalism: A Global History. Penguin UK, 2014.

Josephy Jr., Alvin M. “The American Indian and Freedom of Religion: An Historic Appraisal.” Terra Northwest: Interpreting People and Place. WSU Press/Washington State University Press, 2007.

Killen, Patricia O’Connell, and Mark Silk. Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone. Vol. 1. Rowman Altamira, 2004.

Lichatowich, Jim. “Salmon without Rivers: a History of the Pacific Salmon Crisis.” 1999. Island Press.

Malone, Nicholas, and Kathryn Ovenden. “Natureculture.” In The International Encyclopedia of Primatology, 1–2. American Cancer Society, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119179313.wbprim0135.

Molinero, Luisa, and Supervised Enrique Alonso García. “The Meaning of Salmon in the Northwest: A Historical, Scientific and Sociological Study,” n.d., 128.

PBS. Food – Lummi Nation First Salmon Ceremony, 2018. Oregon Field Guide. Season 25, Episode 2509. PBS. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2LaL337kPs.

Preus, J. Samuel. Explaining Religion. Yale University Press New Haven, CT, 1987.

Salmon Nation. “Salmon Nation – Welcome Home.” Accessed December 16, 2020. https://salmonnation.net/?post_type=wpcf7_contact_form&p=8.

Shibley, Mark A. “Sacred Nature: Earth-Based Spirituality as Popular Religion in the Pacific Northwest.” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature & Culture 5, no. 2 (June 2011): 164–85. https://doi.org/10.1558/jsrnc.v5i2.164.

Spirits of the West Coast Art Gallery Inc. “The Salmon Symbol.” Accessed December 3, 2020. https://spiritsofthewestcoast.com/collections/the-salmon-symbol.

Taylor III, Joseph E. Making Salmon: An Environmental History of the Northwest Fisheries Crisis. University of Washington Press, 2009.

Todd, Douglas. Cascadia: The Elusive Utopia: Exploring the Spirit of the Pacific Northwest. Ronsdale Press, 2014.

White, Richard. The Organic Machine: The Remaking of the Columbia River. Macmillan, 1996.